Two boys take part in the Euromaidan demonstrations on 1 December 2013. Photo: Alexandra Gnatoush

The article was firts published at Medium.com.

Political philosopher Mykhailo Minakov discussed with Hromadske’s Nataliya Gumenyuk a recent UNDP survey made in conjunction with the International Institute of Sociology, outlining the three elements of civility in Ukraine: Civic knowledge, participation in civic practices, and values.

“We as Ukrainians really have problems with understanding our rights,” says Mykhailo Minakov, political philosopher and UNDP expert.

As reported by Minakov based on a recent UNDP survey, over 50% of Belarusians believe that the right to life is a core civic right, while in Ukraine and similarly in Moldova, citizens believe the right to have a job is most important. His theory is that nations who have experienced a war have a different understanding of what the right to life is. The survey outlined significant gaps in the knowledge of state structure, legal framework, citizens’ rights and duties among Ukrainians.

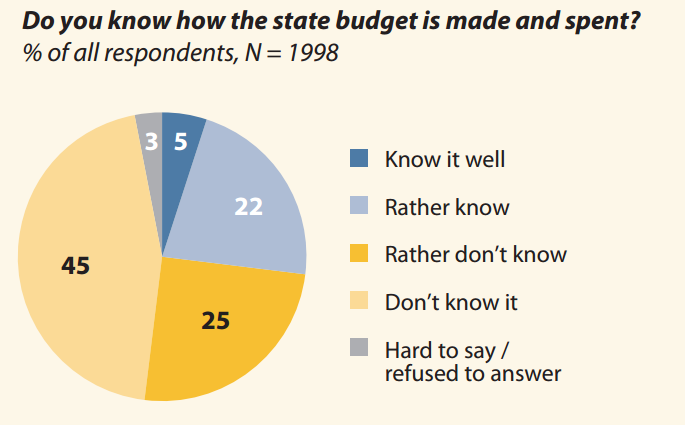

The hardest questions for Ukrainians concern knowing their representatives in the elected authorities and personal income taxation. Only every fourth Ukrainian knows a member of local council or a political party which nominated him, or is aware that the personal income tax rate is 18%.

When it comes to the duties of citizens, it’s harder to the respondents to mention them compared to the rights, because they have more expectations from the state than from themselves. The most important duties were to abide by the law and order (32% of respondents), and pay taxes (21% of respondents).

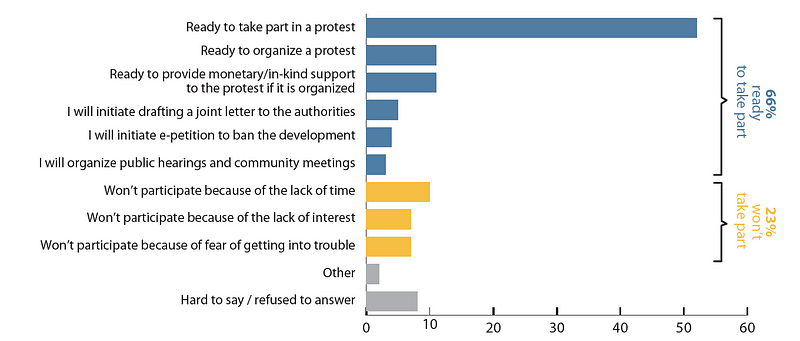

More than a half of respondents in Ukraine (63%) participate in the life of local community in any form — take part in land improvement, joint activities with the neighbours, meetings of residents and house owners, etc. The majority of them are ready to join protests against toxic industrial development and especially land improvement. However, respondents prefer participating rather than organizing such activities and only 2% of Ukrainians confirmed readiness to organize them.

Respondents tend to rest responsibility for their employment, education, health and financial well-being on themselves rather than on the government. At the same time, they are quite pessimistic about their ability to exert any influence on the life in their city/village, country or abroad, and most people don’t feel like having any leverages to impact anything beyond their family.

Some barriers to community participants noted by experts are laziness and lack of interest, distrust to collective action, lack of confidence, disappointment by the results of protests and loss of trust that citizens can make a difference.

“There are two more fundamental reasons for the low level of civic activism”, Minakov said. “Firstly, there is no leaders who can undertake responsibility; secondly, the paternalistic attitudes are strong. Furthermore, the people tend to be suspicious and distrustful towards the activities of civic initiatives and NGOs, as they are often accused of being paid up or linked to politicians”.

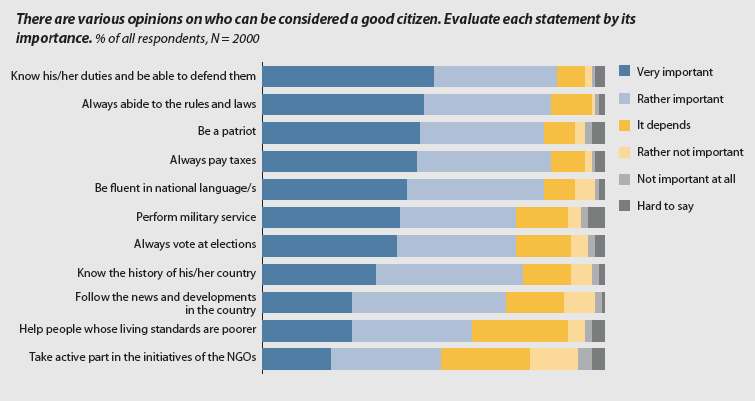

Values considered most important are: respect to human life, human rights, social justice, and law-obedience. Respondents almost equally believe that the features of a good citizen are: always abide by the law, pay taxes, know his/her duties and rights, and protect them.

Notwithstanding the declared respect to human rights, many respondents support contradictory statements. It might mean both poor understanding of questions by the respondents, and contradictory beliefs or immature sets of attitudes in the majority of people.

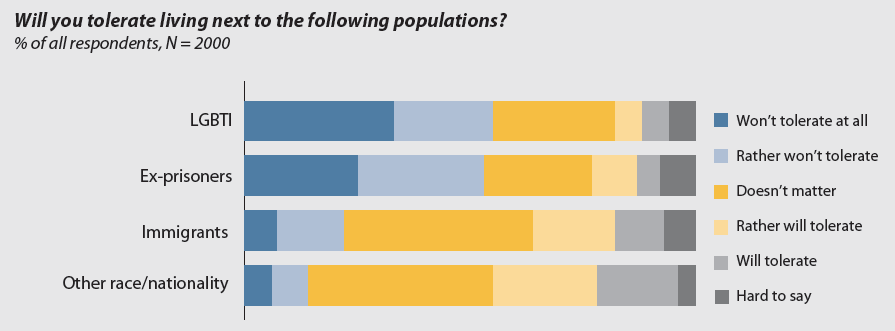

In all three countries, 50% or more respondents who had picked tolerance as a personally important value reported that they would not accept living next to gay people or other sexual minorities.

The survey also shows that in Ukraine there is a demand for more civic education in the country (47% of respondents).

“There is a demand for more civic education, but there is no supply,” adds Minakov.

The most demanded practical skills are: to protect own rights and interests, critical thinking, and starting-up and running own business. The preferred ways to receive necessary knowledge and skills are online and attending training programmes and workshops in-person. Respondents prioritize governmental training programmes and self-education.

The report “Civic Literacy in Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus” was prepared by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) for the UN Development Programme in Ukraine (UNDP) supported by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It provides an account of the representative public opinion survey carried out in 2016 by the KIIS in Ukraine, CBS-AXA in Moldova commissioned by UNDP and SBTC SATIO in Belarus commissioned by Pact Inc.