UDI Advisor and Associate Wolfgang Merkel, Social Science Research Centre Berlin (WZB)

UDI Advisor and Associate Wolfgang Merkel, Social Science Research Centre Berlin (WZB)

This article is part of the Democracy Futures series, a joint global initiative with the Sydney Democracy Network. The project aims to stimulate fresh thinking about the many challenges facing democracies in the 21st century.

Asked whom he would vote for on November 8, 2016, if he were an American, the man responded without hesitation:

Trump. I am just horrified about him, but Hillary is the true danger.

The respondent was none other than Slavoj Žižek, the neo-Marxist philosopher and pop star of the internet. It is safe to assume that Žižek could only have been left aghast by his own endorsement on the morning after the election.

‘In every society there is a whole network of unwritten rules – how politics works, how you build consensus – Trump disrupted this.

The unspeakable has happened: on November 8, Donald Trump was elected the 45th president of the United States. The bankrupt New York billionaire, the sexist chauvinist, the man with the baseball cap and the bad manners, the big-mouth Me Inc is now the most important politician of the (Western) world.

Will he have as catastrophic an impact on the world as his Republican predecessor, George W. Bush, did? What can be said about the campaign, the election, Trump’s political program and the state of democracy in America? Is Trump an American phenomenon or does the US merely hold up to Europeans a mirror of their future, as Alexis de Tocqueville once wrote in Democracy in America?

Is Trump’s election the revolt of those who have long felt unrepresented by established politics, by the “political class”, by the media, by the public discourses and by an economic system that is generating increasing inequality? Will right-wing populism now spread across the Atlantic and spill back into Europe?

What does the campaign tell us?

One of the core arguments of the theorists of post-democracy, from Colin Crouch to Jacques Rancière, is that elections in the post-democratic age have degenerated into empty rituals. They are not the heart of democracy, only its mere simulation. The policy contents do not matter; and if they do, the “competing” political programs are indistinguishable from one another.

As with many a thesis on post-democracy, this one is only half-true. Political programs were not of much significance in this election – neither in the campaign speeches nor in the media coverage.

Instead, personal attacks and mudslinging took centre stage: “crooked Hillary”, “corrupt Hillary”, who belongs in prison and not in the White House, who lies, cheats and enriches herself with her husband – either through her commingling of non-profit foundations and private speeches that generated millions for Bill Clinton in Qatar, or from representatives of Wall Street.

The Democratic candidate returned the attacks in kind: “Donald” is a sexist, racist chauvinist who harasses women, insults Muslims, mocks the disabled, calls Latin American immigrants rapists, discriminates against African-Americans “like his father did” and, to top it all off, chronically evades tax.

Hillary Clinton slammed Donald Trump’s long record of racism in the first presidential debate.

Certainly, the history of democratic elections reached a new low in the American autumn of 2016.

What does not hold water in the post-democracy thesis is that there are no programmatic differences. The electoral programs of Trump and Clinton were quite different.

Trump adheres to old neoliberal formulae: cut taxes so that investors invest, the economy grows and the jobs come back from Mexico, China, Japan and Europe. His policy proposals follow the famous napkin sketch with which Reagan’s chief economist, Arthur B. Laffer, convinced the then-president that tax cuts lead not only to investment and GDP growth, but also to greater tax revenues.

George W. Bush, another economic layman, applied the deceptively simple formula again a decade later.

In both cases, the policy led to the greatest rises in public debt that American democracy had ever witnessed. And now, with Trump, the fiscal policy tragedies threaten to repeat themselves as farce.

In 1974, economist Arthur Laffer kick-started supply-side economics with a simple sketch.

The welfare state in the US is underdeveloped. There are historical reasons for this: the sanctity of private property, the ideology of the minimal state, the weakness of the trade unions, the lack of a labour party, and the establishment of a particularly rugged, unbridled form of capitalism.

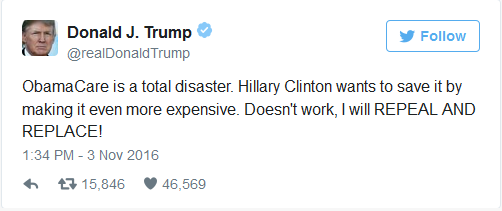

One of the successful reforms of Obama’s presidency was the creation, in the face of rabid opposition from the Republicans, of access to health insurance for the lower classes through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. For Trump, “Obamacare” is a “disaster”. The new president, with the solid backing of his electorate, will do everything it takes to undo even these modest social reforms.

In the realm of foreign trade, Trump’s proposals have much ado in store, if not the risk of an all-out trade war. The billionaire is simultaneously offering to his citizens and menacing the rest of the world with a strange mix of neoliberal deregulation at home and protectionist threats abroad. China, Europe and the “disaster NAFTA” are to blame for job losses, according to the simple worldview of the Republican populist.

Free-trade agreements are to be rescinded and products from Asia and Europe tagged with punitive tariffs if they run contrary to American economic interests.

But the biggest question marks are in foreign policy. Trump, a complete layman, has shown no recognisable profile up to this point.

Clinton, on the other hand, was clearer – both in word and unfortunately also in deed. She is a hawk among the Democrats, one who supported the illegal, deceitful war on Iraq under George W. Bush and called for the expansion of the UN mandate against Gaddafi’s Libya.

The consequence was not only an unmandated “regime change”, but also, as was already the case in Afghanistan and Iraq, the destruction of an entire country’s statehood – a serious mistake with long-term consequences indeed.

Power, as the Austrian-American political scientist Karl Deutsch once said, is the “ability to afford not to learn”. On Russia, the then-secretary of state followed the Cold War logic of “containment”, but also of the continued humiliation of the former world power. This was not a far-sighted policy, neither for Ukraine nor for Europe, Germany or détente in general.

Trump, on the other hand, expressed sympathies for Putin during the campaign, something that is considered close to a capital offence in the US. Whether this merely amounted to male bonding between authoritarian personalities or signalled the beginning of a new politics of rapprochement remains to be seen.

For China and Europe, however, things may get uncomfortable. The US may well demand from Europe a greater share of financial contributions to NATO, armaments and military operations. The targeting of European businesses for legal action – a popular form of American industrial policy – could enter the next round under Trump.

Whether Trump will attempt to fight China’s authoritarian-statist policy of goods and capital export remains to be seen. Here, the US may, once again, come to appreciate the meaning of “imperial overstretch”.

On democracy in America

Trump has won the election. Further, the Republicans have the majority in both the Senate and the House. The semi-democratic winner-takes-all system of the archaic electoral college made this threefold victory possible.

Clinton won, as did Al Gore against George W. Bush, a slim majority of the popular vote, which translated into a clear defeat under the electoral college system.

While Trump won 290 electoral votes, with at least one state in doubt, Hillary Clinton received just 232. The turnout at the presidential election stands at a meagre 56.9%; the turnout figures for the Congressional elections, which are traditionally even lower, are not yet available.

Pippa Norris, the renowned scholar of democracy and elections at Harvard University, has examined the integrity of elections in democracies and autocracies for many years. In her ranking of 153 countries, the US finishes just 52nd. Ahead of the US are countries like Croatia, Greece, Argentina, Mongolia and even South Africa.

Reasons for the lower integrity of US elections include:

- the massive influence of wealthy private donors on electoral campaigns and programs;

- frequent gerrymandering;

- a voter registration system that de facto discriminates against lower classes and African-Americans in particular;

- extremely low turnouts at Congressional elections;

- a winner-take-all electoral system; and

- the shamefully low number of polling booths in a technologically and economically advanced country like the US. Long queues like those in Bangladesh are a common sight in US elections.

However, American democracy is known for its extensive “checks and balances”. Checks on power, in particular, are strongly developed: congressional majorities are not automatically of the same party as the president; the federal government has a relatively weak position vis-à-vis individual states under the US federal system; and the Supreme Court is one of the most powerful constitutional courts in the world.

Congressional control of the executive will, however, be initially weak if Trump succeeds in bringing the Republican Party establishment in line after their previous falling-out. Trump has also made it clear he will nominate a hand-picked conservative candidate for the Supreme Court vacancy. The current political constellation, then, means fewer constraints on President Trump than was intended in the US Constitution.

In this context, the “mainstream media” (according to Trump) and the civil-society watchdogs will have an important oversight role to play. What cannot be expected in the coming years, however, is a boost for democracy and tolerance in the American polity.

Is Trump a truly right-wing populist?

Is Trump actually a right-wing ideologue, or is he merely a demagogic populist campaigner who could be reined in by institutions, by his advisers and by public opinion once in office?

To start, Trump is considered fairly resistant to advice. Also, counterbalancing institutions are less effective in populist times and with a presidential majority than what constitutional theory would have us believe.

More important is the question: who are the voters behind Trump? What do they mean for democracy?

Initial analysis suggests that Trump has disproportionately large shares of the vote among male, less educated, white, non-urban voters. They are the losers of economic globalisation and belong to the socioeconomically lower half of American society. This is the America that is demographically, economically and culturally under threat.

It is doubtful, however, that the economic situation was the driving motivation behind the Trump vote. In other words: it’s not the economy, stupid!

There are parallels here to right-wing populist parties in Western and Eastern Europe. The established political forces, the media, the progressives, the better-to-do and the chorus of “reason” are all too often content with merely representing their own interests and their cultural modernity.

Conservative fears of a “loss of Heimat [homeland]”, of the city district, of the familiar culture, of the nation, of state sovereignty, of the meaning of borders, or of traditional conceptions of marriage have been countered with moral condescension, or even exclusion from official discourse in cases where “incorrect” terms or ideas were expressed.

All too often, a cosmopolitan spirit with a sanctimonious sense of morality has dominated the discourse. Just as Brexit supporters are said to be from the world of yesterday and to not understand today’s world of supranationalisation, the voters of right-wing populist parties are held to be the moral and cultural laggards of society.

In Western Europe, right-wing populist entrepreneurs have now captured in these “laggards” some 10-30% of the electorate. Right-wing populism has shown its ability to win majorities in Poland and in Hungary – and now in the US, the supreme global democratic power.

Yet not all Trump supporters are anti-democratic racists, sexists and chauvinists, and not all of them belong to the lower classes. What is disturbing all the same is that Candidate Trump benefited rather than suffered from his use of intolerant slogans against the establishment, against the “political class in Washington”, “those at the top” and those for “change”.

Symptomatic was the closing rally of the Democratic campaign on November 7 in Philadelphia: with Obama, the First Lady, ex-President Bill Clinton, Bruce Springsteen and Jon Bon Jovi, it featured an impressive array of the establishment on stage. None of this prevented the majority of Pennsylvania voters from voting for the outsider, Donald Trump.

Even money did not buy Hillary the electoral victory. She spent two or three times as much on her campaign as Donald Trump did on his.

Sarah Burris/flickr

We, the better-to-do and the established of civil and political society, have become sedate, complacent and deaf to “those at the bottom” – economically as well as culturally. The working class has gone over to the right-wing populists.

We have come to defend existing conditions, whereas the right has taken up our former battle cries of change. The electoral success of Trump must therefore also be interpreted as a warning sign.

A representative democracy must represent each and every one to the extent possible. It must also permit reactionary or conservative criticisms that transgress the supposed bounds of political correctness.

This should not detract from our determined advocacy of freedom, equality and the cultural progress of the past decades. On the contrary: these must be defended. However, preaching from above, moral intransigence and the discursive exclusion of the “non-representable” only plays into the hands of the right-wing populists.

This article was translated from German by Seongcheol Kim, WZB and Humboldt University.

Wolfgang Merkel, Professor of Comparative Political Science and Democracy Research at the Humboldt University Berlin; Associate of the Sydney Democracy Network, University of Sydney; Director of Research Unit Democracy: Structures, Performance, Challenges, Social Science Research Centre Berlin (WZB)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.