Michael Averko analyses the making of political statements at international public platforms in the context of Ukraine’s choice of the song for the Eurovision and Crimean Tatars. First published in Strategic Culture Foundation.

At Stake

The February 21 Associated Press (AP) article has the tabloid title of “Ukraine’s Eurovision Entry Takes Aim at Russian Oppression.” Covering much of the same points in a similar manner, the February 23 Washington Post (WaPo) article has the debatable title of “Ukraine’s Eurovision Entry is a Dig at Russia and it isn’t Very Subtle.”

The AP and WaPo articles note that Eurovision has a policy of not accepting performances with overt political content. Ukraine’s 2016 Eurovision contestant Jamala (Susana Jamaladinova) and whoever her handlers might be, have crafted a performance that can be presented as historical and not political, with the premise that she has the right to politically express herself away from Eurovision. Hence, the content in the Ukrainian Eurovision selection is somewhat subtle, for the obvious intent of skirting the Eurovision prohibition on overt political performances.

Jamala’s song is about the collective Soviet WW II era deportation of the Crimean Tatars. Post-Soviet Russia has formally acknowledged the wrongness of that action.

Jamala and 2004 Eurovision winner Ruslana (one of the Ukrainian judges, who selected Jamala for the upcoming Eurovision contest), have openly expressed negativity towards Crimea’s reunification with Russia in 2014. Concerning Jamala’s song, Crimean Tatar activist Mustafa Dzhemilev, is quoted in the AP article saying:

“There’s no mention there about occupation or other outrages that the occupants are doing in our motherland; nevertheless, it touches on the issue of indigenous people who’ve undergone horrible iniquities.”

The selection of this song definitely appears to be politically motivated, with content that could very well achieve Eurovision acceptance.

The WaPo article notes how some Russian politicians have responded to Ukraine’s Eurovision selection. In terms of public relations, it’s (IMO) best for Russia to not issue a formal protest to Eurovision. If no such Russian complaint is made, there’s likely going to be little if any Western mass media recognition of Russia taking the high road. The inaccurately negative perception of Russia in the West can get even worse. There’re constructively intelligent ways to support the mainstream Russian position on Crimea.

Meantime, it’s a good idea for Russia and its supporters not to give the Kiev regime any propaganda fodder. Pro-Russian advocacy can walk and chew gum at the same time in the form of acknowledging the past Crimean Tatar suffering and correctly detailing how post-Soviet Russia isn’t the Soviet Union.

Past Political Occurrences at Major International Gatherings

Should Eurovision choose to accept Jamala’s song, it’d be hypocritical to deny an Armenian entrant’s performance that brings up the WW I Genocide of the Armenians. Like Eurovision, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the numerous sports federation linked to it, prefer to not have politics brought into their events.

At the opening ceremony of the 1976 Montreal Summer Olympics, the Israeli delegation marched into the stadium wearing black ribbons to honor their murdered brethren at the 1972 Munich Summer Olympics. That move concerned a not too distant tragedy involving the prior Summer Olympics – and as such is different than if the 1972 Israeli Olympic delegation marched into the Munich opening ceremony wearing black to commemorate the Nazi instigated WW II Holocaust. In 1972, Israel showed respect at Munich by not highlighting the Nazi past at an Olympic opening ceremony, that’s ideally intended to be festive.

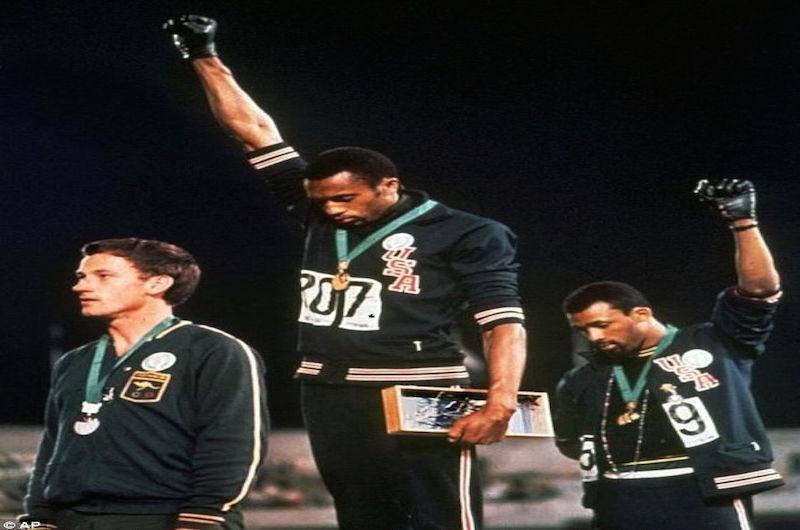

In more recent times, Serb swimmer Milorad Cavic was suspended from the 2008 European Aquatics Championship for wearing a “Kosovo is Serbia” t-shirt at the awarding of his first place finish. This was akin to what 200-meter gold and bronze medalists (respectively) Tommie Smith and John Carlos did at the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics – when they gave a clench fisted black power salute during the playing of the US national anthem.

There can be sympathy with the American civil rights movement and the mainstream Serb position on Kosovo, while not necessarily agreeing that these subjects should be highlighted at the awards ceremonies at major international sporting events. Some might take issue with likening the Carlos-Smith expression with Cavic’s. That thought leads to determining which political advocacy is more legitimate.

A Further Look at the Crimean Tatar Issue

The February 9 Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty piece “Crimean Tatar Singer Hopes to take People’s Tragedy to Eurovision,” quotes Jamala stating:

“Now the Crimean Tatars are on occupied territory. And it’s very hard for them. They’re under tremendous pressure. Some have disappeared without a trace. And that’s terrifying. I wouldn’t want to see history repeat itself.”

How numerous and well documented are these disappearance? The question is asked without meaning to belittle the matter, while noting a reasonable cause for suspicion on how this particular has been communicated. A given disappearance can be for a reason unrelated to the Crimean government and/or rogue pro-Russian elements. Taking the form of either an exaggeration or outright lie, crock human rights related claims have been made in the past to gain worldwide support. A quick whataboutism on terror notes the rate of violence in Chicago, which has about a half million more population than Crimea.

A noticeable number of Tatars have left Crimea since its changed territorial status, with the overwhelming majority of them staying. There’re varied figures stated on the number of Tatars and non-Tatars who’ve left Crimea within the last two years. On this score, the commonly presented figures range between 20,000 and 50,000 – less than 5% of Crimea’s pre-reunification total population.

It’s not unreasonable to surmise that many of the Crimeans departed are ardently opposed to a pro-Russian orientation, with a fear of living in Russia, as opposed to experiencing persecution. Not to be overlooked are the Crimeans looking to go to the West – a desire found in varying degrees throughout the former Soviet Union.

The parallel instance of pro-Russians in Kiev regime controlled areas not feeling secure with the two regimes that succeeded the deposed Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych is quite real. With Russia as a prime destination, there has been a noticeable exodus of these people. Western mass media analysis tends to suggest that pro-Russian activity is suspect and therefore more deserving of persecution than anti-Russian manner.

With Samantha Power in mind, the coverage accorded to the Odessa massacre of 46 pro-Russian activists by their political opposites serves as one example. Imagine the outcry if pro-Kiev regime Crimean Tatars were chased into a building and killed thereafter by an unruly pro-Russian mob, with evidence of some law enforcement complicity in that act, as what occurred in Odessa. What happened in Odessa isn’t just one isolated instance in Kiev controlled Ukraine.

There’ve been periodic Western reports that highlight a not so smooth Crimean transition to Russia. Not as highlighted is the reality that Crimean opposition to Crimea’s reunification with Russia remains a noticeable minority, on account of the comparatively (to Russia) direr socioeconomic conditions in Kiev regime controlled Ukraine – in addition to the increased anti-Russian activity in that part of the former Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Despite having problems, Crimea doesn’t appear to be on the verge of a major race war, with some Crimean Tatars accepting the reunification with Russia.

“As is true with any large country of varying ethno-religious groups, Russia isn’t without tensions and room for improvement. Things there aren’t as bad as propagandistically stated in some influential to relatively influential Western circles.

Many people of Muslim background from Central Asia and the Caucasus have migrated to the mostly Slavic inhabited northwestern part of Russia, for a better life. The Russian republic of Tatarstan has gotten good reviews, as an example of multi-ethnic/confessional tolerance. The negatively depicted Putin has condemned the WW II punishment of the Crimean Tatars. In comparison, the pro-Kiev regime Crimean Tatar activist Mustafa Dzhemilev is on record for saying that the Russians should leave Crimea.”

In the February 21 AP piece, Dzhemilev describes the Crimean Tatars as being indigenous to Crimea. Typically omitted from this characterization (which has made the rounds) is a broader and more accurate portrayal of Crimean history, which reveals that its Tatar presence isn’t so indigenous as suggested. Part of Crimean territory became affiliated with the medieval state of Rus, which modern day Russia, Ukraine and Belarus trace their origin to. Later on, the Tatars settled in Crimea. The Tatar Khanate in Crimea established a slave trade against Slavs and some others. Crimea became part of the Russian Empire in 1783.

The 1897 Russian Empire census of Crimea lists Tatars as constituting 35.5% of the region’s population, with Russians at 33.11% and Ukrainians at 11.84%. In 1939, the Soviet census of that region put the Tatars at 13.7%, Russians at 49.6% and Ukrainians at 19.4%. The 2001 post-Soviet Ukrainian government census of Crimea shows 10.8% Tatar, 60.4% Russian and 24% Ukrainian. In 2014, the Crimean census compiled after Crimea’s reunification with Russia, has a breakdown of 12.2% Tatar, 65.3% Russian and 15.7% Ukrainian.

During WW II, the Soviet government exiled the Crimean Tatars to Central Asia under inhospitable conditions. The rationale behind this treatment (having to do with the ethically challenged notion of a collective ethnic disloyalty during war), is similar to what Japanese-North Americans faced at the time. The latter had much better conditions, due to the more desirable wartime socioeconomic circumstances in North America and the different political situation between the Soviet Union and North America.

Dzhemilev’s being banned from Crimea is essentially part of a tit for tat process that sees some pro-Russian Crimean political figures legally threatened by the Kiev regime, in addition to their being banned from pro-Kiev regime Western countries. This status quo is only likely to change when the Russian and Ukrainian governments reach enough of a common ground with each other – something that seems distant for now.

A stark contrast to the opinions of Jamala and Dzhemilev is presented in the February 11 Consortium News article “How Crimeans see Ukraine Crisis» and the February 23 Russia Insider piece «Move Over Conchita – Ukraine to Rock Eurovision Fans With Pentagon Sing-A-Long.”