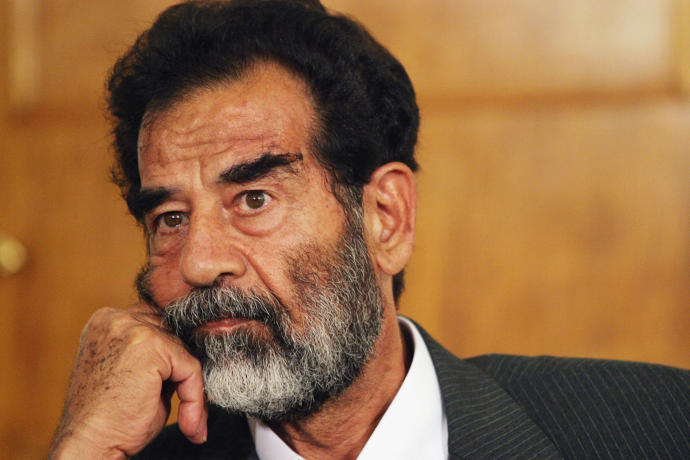

PHOTOGRAPH BY POOL / GETTY

The article was first published by The New Yorker.

While the connection between the war to depose Saddam Hussein and the election of 2016 is indirect, it is etched in history.

s the members of the Electoral College gathered across the country on Monday, to elect the next President, there was another rash of articles seeking to explain how an untested candidate, whose approval rating stood at 37.5 per cent on November 8th, had managed to defeat an opponent who was a former First Lady, U.S. senator, and Secretary of State. But the piece that caught my eye wasn’t directly tied to the election. It was a gripping review in the Times of a new book by John Nixon, a former C.I.A. officer, who was the first agency official to interview Saddam Hussein after American forces captured him hiding in a hole in the ground near the Iraqi city of Tikrit, in December, 2003.

Bear with me, though. While the connection between the war to depose Saddam and the election of 2016 is indirect, it is etched in history. Without the invasion of Iraq, and the disillusionment with the U.S. political establishment that its terrible aftermath created, it is hard to see how a demagogue like Trump could ever have gained traction in national politics.

Yes, many factors played into his rise to power: deindustrialization, stagnant wages, racial resentments, class resentments, sexism, a craven broadcast media that gave him huge amounts of free airtime, strategic blunders by his opponent and her campaign, and the last-minute intervention of James Comey, the director of the F.B.I. Indeed, the problem with trying to explain Hillary Clinton’s defeat is that it was overdetermined: all sorts of arguments can seem persuasive. But the popular perception of a world gone haywire, a perception that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan helped to create, was also an important factor. You can tell the American people all day long that ISIS is on the retreat and that, statistically, the threat of getting killed in a terrorist attack is very small. But when Trump said, during the campaign, “We don’t win anymore,” it resonated. When he promised to “smash” ISIS, he was telling people what they wanted to hear.

Trump also criticized the war in Iraq as a pointless venture during his campaign, although he had expressed support for it at the time. Nixon’s book, “Debriefing the President,” gives more ammunition to the skeptics; indeed, some of its contents can only be described as sensational. It asserts, for instance, that by the time the invasion took place, in March, 2003, Hussein wasn’t really running Iraq anymore. “Hussein had turned over the day-to-day running of the Iraqi government to his aides and was spending most of his time writing a novel,” James Risen, a veteran intelligence reporter for the Times, writes in the review. “Hussein described himself to Mr. Nixon as both president of Iraq and a writer, and complained to Mr. Nixon that the United States military had taken away his writing materials, preventing him from finishing his book.”

Saddam could have been lying to try to save his skin, of course. But Nixon believed him, and he was in a better position than most to assess the truth. After studying the Iraqi regime in graduate school, he had spent five years as a C.I.A. “leadership analyst” on Iraq. Nixon knew so much about Saddam that, after the capture, he was brought in to confirm his identity. (A scar and a tattoo gave the Iraqi strongman away.) In Nixon’s telling, by 2003, far from preparing to unleash a flurry of weapons of mass destruction against U.S. allies in the Middle East, Saddam was busy deferring to his Vice-President, Taha Yassin Ramadan. “Was Saddam worth removing from power?” Mr. Nixon writes. “I can speak only for myself when I say that the answer must be no. . . . He was no longer running the government.”

It is hard to exaggerate the scale of the disaster that Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Blair, Powell, et al. unleashed. Between 2003 and 2011, according to a 2015 study by a team of academic researchers from the United States, Canada, and Iraq, the war and its aftermath caused almost half a million deaths among Iraqis and people who fled the country. Not all these fatalities were the result of gunshots or explosions—they were also due to ingesting contaminated water, or conflict-related stress, or the fact that hospitals had been overburdened or destroyed. But they were still deaths that could have been avoided if the invasion hadn’t taken place, the researchers concluded.

That is just the toll on Iraq. Close to seven thousand members of the American military have died in Iraq and Afghanistan. And, in overthrowing Saddam and then failing to pacify Iraq, the U.S.-led coalition ended up destabilizing the entire region, with tragic consequences that are still playing out in Syria, Egypt, Libya, Turkey, and lots of other places. To be sure, the Iraq invasion didn’t create Islamic extremism or the Sunni-Shiite schism. However, as I noted in 2014, as ISIS cemented its grip on Mosul, the invasion “opened Pandora’s Box.” Which brings us back to Trump.

He hasn’t got any real solutions to offer, of course. A classic demagogue, he offered up reassuring slogans and few specific proposals. In putting together his foreign-policy team, he selected (or seriously considered) people with strong a-priori views, clear ideological biases, a disdain for careful intelligence work, and a willingness to demonize individual regimes—people like retired Lieutenant General Michael Flynn (Trump’s pick for national-security adviser), David Friedman (his pick for Ambassador to Israel), and John Bolton (who is reportedly being considered for a top job at the State Department).

We are all too familiar with where these types of attributes and individuals can lead a country. After 9/11, Nixon’s book says, Saddam, a secular dictator who feared the rise of religious fanaticism, hoped Iraq and the United States could come together and coöperate against Al Qaeda and its offshoots. “In Saddam’s mind, the two countries were natural allies in the fight against extremism . . . and, as he said many times during his interrogation, he couldn’t understand why the United States did not see eye to eye with him.” The reason was straightforward. The Bush Administration, for reasons of its own, had decided to overthrow him in an international show of force.

In Iraq and Syria today, the United States is tacitly coöperating with another dictatorial regime, Iran, in the war against ISIS. While progress has been slow, it has also been steady, and ISIS fighters have been forced to give up a good deal of ground. Trump will have to decide whether to continue on with this course or follow the advice of some of his advisers and adopt a much more confrontational stance against Tehran.

It is to be hoped that he chooses the first option. In any case, though, he won’t be able to escape the poisonous legacy of March, 2003, which now looks like one of history’s turning points. And he’ll quickly find out what President Obama must surely have impressed on him during their recent conversations: simple solutions are chronically lacking.

John Cassidy has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1995. He also writes a column about politics, economics, and more for newyorker.com.